Q&A with Gustavo Marulanda, Director of IGAC, Colombia’s cadaster and mapping agency

USAID’s Land for Prosperity Activity is updating the cadaster of 11 municipalities in eight regions of Colombia and the Chiribiquete National Park, the largest protected area in Colombia, to support formal land markets and protect biodiversity. In this interview, Gustavo Marulanda, IGAC’s Director, talks about the cadaster as an essential component of property formalization and regional land administration.

USAID’s Land for Prosperity Activity is updating the cadaster of 11 municipalities in eight regions of Colombia and the Chiribiquete National Park, the largest protected area in Colombia, to support formal land markets and protect biodiversity. In this interview, Gustavo Marulanda, IGAC’s Director, talks about the cadaster as an essential component of property formalization and regional land administration.

How up-to-date is Colombia’s rural cadaster?

Approximately 905 of the country’s 1,101 municipalities have an outdated cadaster, and some were updated 30 years ago. This means that there are people that are only paying a small percent of what they should be paying in property taxes. The average property tax payment is just COP $28,000 (USD $7). This is what everyone pays, not just smallholder farmers but also the large landowners. So, updating the cadaster allows us to make significant progress with the process of promoting equality and improving tax redistribution.

How does updating the cadaster help with the implementation of the Peace Accords?

Point 1 of the Peace Accords is comprehensive rural reform, and an updated cadaster is fundamental here. The Peace Accords aim to formalize seven million hectares and redistribute three million hectares, but the first thing we need to achieve this is detailed property information, to know who are owners and who are occupants. By updating the cadaster, we can achieve more equity in the distribution of land. For example, many of the large landowners in the country, who often have unproductive and unused land, are not paying property tax.

How does the IGAC support land formalization?

At IGAC we have a legal responsibility to know the current and allowed land uses, we have to know what each piece of land is good for and how we need to protect it. The cadaster is the map of landowners who have secure tenure rights to their property. The cadaster generates knowledge and detailed information about our rural territories and provides us with inputs that are fundamental to administer land and property in a way that is socially responsible and promotes sustainable land use and production.

At IGAC we have a legal responsibility to know the current and allowed land uses, we have to know what each piece of land is good for and how we need to protect it. The cadaster is the map of landowners who have secure tenure rights to their property. The cadaster generates knowledge and detailed information about our rural territories and provides us with inputs that are fundamental to administer land and property in a way that is socially responsible and promotes sustainable land use and production.

How do the communities benefit from the cadastral update?

Citizens benefit from the cadaster when they ask themselves things like “Where is my farm located? What are its boundaries? Who are my neighbors?”. It is similar to opening your smartphone and using mapping and navigation apps to know your location. An updated cadaster allows the municipality to make better decisions and to know where its population lives and what their needs are. The municipality knows if there are schools, health centers, or where to build infrastructure such as roads in a more efficient way. Additionally, by collecting property taxes, the municipality will increase its budget. The cadaster ensures that taxes are fair, so the ones who have more, pay more. Today no one is paying, neither the ones who have the most nor the ones who have the least.

How have you involved citizens more in these topics?

Before, the community was not actively involved and that was a problem. That is why our logic is that the cadaster is made for the people and with the people. This is advantageous, because we can explain to the public why the cadaster is useful. People say “they update the cadaster and then my taxes increase, so I will have to pay more”, but they forget that they are also supporting land formalization and will receive a property title. And without a title they cannot access loans or subsidies.

Before, the community was not actively involved and that was a problem. That is why our logic is that the cadaster is made for the people and with the people. This is advantageous, because we can explain to the public why the cadaster is useful. People say “they update the cadaster and then my taxes increase, so I will have to pay more”, but they forget that they are also supporting land formalization and will receive a property title. And without a title they cannot access loans or subsidies.

What are the Intercultural Cadaster Schools that USAID is supporting in Chiribiquete about, and how are they connected to the communities?

When we talk about the cadaster with the communities, we have to work with people, empower them, engage them with all these messages so they can make significant contributions to the information collection process and its sustainability. This is what the Intercultural Schools are doing, under the Geography for Life motto. They learn mapping exercises in an effective way, they understand why it is useful and how the community fits into their territory. Through mapping, communities can get to know their surroundings better and strengthen their spatial relationships. Sustainability is only achieved when people are empowered.

How does the cadaster contribute to conservation and environmental protection?

The information collected through the multipurpose cadaster contributes to the defense of strategic ecosystems in our country and continent, because we are connected to the Amazon and to the rivers that flow through it. This is why we have to know about them, their location, and have detailed information that allows us to make better decisions to defend and protect the environment. We have to monitor the levels of deforestation and illegal mining to defend our regions effectively.

How does the IGAC work with other government entities for land formalization?

In Colombia, the land administration trio of agencies includes IGAC, the National Land Agency (ANT) and the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR). IGAC is responsible for collecting and managing detailed information, and in areas that have been prioritized by the government, we receive support from the ANT as a cadastral operator. The ANT then administers the land that has been formalized or that will be redistributed and continues with the formalization and title delivery processes. The cycle then finishes with the SNR, which registers and issues the land titles.

In Colombia, the land administration trio of agencies includes IGAC, the National Land Agency (ANT) and the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR). IGAC is responsible for collecting and managing detailed information, and in areas that have been prioritized by the government, we receive support from the ANT as a cadastral operator. The ANT then administers the land that has been formalized or that will be redistributed and continues with the formalization and title delivery processes. The cycle then finishes with the SNR, which registers and issues the land titles.

USAID coordinates inter-institutional cooperation among Colombia’s land administration entities.

Why is the support of international donors important?

Donors, such as USAID, play a vital role, not just because they provide financing, but they also transfer knowledge, best practices, and technical capacities, which make us more efficient. We can also learn from international experiences, of how it has been done in other places or how we can improve information processing. The Intercultural Schools come from international experiences and from what donors have done elsewhere. The Land for Prosperity Activity has carried out property surveys and through trial and error helped to create a lot of the new methodologies we have today. Donors also have an added value because they coordinate institutions, because sometimes we are so busy with our day-to-day tasks that we have no time left to sit down and coordinate actions together.

I am a Project Management Specialist in USAID’s Democracy, Rights, Governance and Conflict Prevention office in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. I joined USAID in September 2021; however, my commitment to the Agency goes back nearly 10 years. Previously, I was involved as a consultant and later as an awardee under the USAID Office of Transition Initiatives, where I helped rebuild broken intercommunal relations after the 2011 post-electoral crisis. During this time, USAID produced a short

I am a Project Management Specialist in USAID’s Democracy, Rights, Governance and Conflict Prevention office in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. I joined USAID in September 2021; however, my commitment to the Agency goes back nearly 10 years. Previously, I was involved as a consultant and later as an awardee under the USAID Office of Transition Initiatives, where I helped rebuild broken intercommunal relations after the 2011 post-electoral crisis. During this time, USAID produced a short

In the last four years, the Municipal Land Office (MLO) of Santander de Quilichao has facilitated the titling of more than 700 parcels. Several of these are public parcels like parks or health centers, or have to do with improving the municipality’s roads. The land office has become a key tool for land use planning and property formalization, and with it, the administration has mobilized more than COP $50,000 million (USD $13.5 million) in public investments.

In the last four years, the Municipal Land Office (MLO) of Santander de Quilichao has facilitated the titling of more than 700 parcels. Several of these are public parcels like parks or health centers, or have to do with improving the municipality’s roads. The land office has become a key tool for land use planning and property formalization, and with it, the administration has mobilized more than COP $50,000 million (USD $13.5 million) in public investments. According to the latest reports, we can say that thanks to the MLO the municipality has mobilized more than COP $50,000 million (USD $13.5 million). We are talking about impactful projects such as building roads, like the Niza road, and communal spaces such as the Plaza de Toros and the Corona Real park. We also bought the parcels for the Santander de Quilichao Hospital, which has mobilized more than COP $35 million (USD $8,750), and the regional campus for the SENA, which resulted in COP $49 million (USD $12,250). The Villa Maria housing project has mobilized COP $10,000 million (USD $2.5 million) and will provide housing for 400 vulnerable families. For Villa Maria, the MLO helped us with the purchase and division of the parcel. In December we already delivered the first 100 property titles.

According to the latest reports, we can say that thanks to the MLO the municipality has mobilized more than COP $50,000 million (USD $13.5 million). We are talking about impactful projects such as building roads, like the Niza road, and communal spaces such as the Plaza de Toros and the Corona Real park. We also bought the parcels for the Santander de Quilichao Hospital, which has mobilized more than COP $35 million (USD $8,750), and the regional campus for the SENA, which resulted in COP $49 million (USD $12,250). The Villa Maria housing project has mobilized COP $10,000 million (USD $2.5 million) and will provide housing for 400 vulnerable families. For Villa Maria, the MLO helped us with the purchase and division of the parcel. In December we already delivered the first 100 property titles. We are going to try to obtain as many titles as possible and meet our goal of 500 property titles. In addition, we have goals with two main roads: La Cañera and Calle Séptima. There are properties in the middle that now belong to private owners, and we are in the process of obtaining them and creating two-laned roads to join two large sectors of the municipality. We also have projects like the hospital and the marketplace. The land office also plays a role in the implementation of our municipal Land Management Plan.

We are going to try to obtain as many titles as possible and meet our goal of 500 property titles. In addition, we have goals with two main roads: La Cañera and Calle Séptima. There are properties in the middle that now belong to private owners, and we are in the process of obtaining them and creating two-laned roads to join two large sectors of the municipality. We also have projects like the hospital and the marketplace. The land office also plays a role in the implementation of our municipal Land Management Plan. Now, with the parcel sweep, land issues are being promoted. The land office has been a source of information for everybody, in terms of providing advice. The MLO is like our guide, and little by little, people understand better the culture of formal land ownership that we are promoting. People are not frustrated anymore with having to contact Bogotá or a lawyer to ask for information on land or property formalization. We have a population with more opportunities and knowledge, and the MLO has given our residents many solutions.

Now, with the parcel sweep, land issues are being promoted. The land office has been a source of information for everybody, in terms of providing advice. The MLO is like our guide, and little by little, people understand better the culture of formal land ownership that we are promoting. People are not frustrated anymore with having to contact Bogotá or a lawyer to ask for information on land or property formalization. We have a population with more opportunities and knowledge, and the MLO has given our residents many solutions.

Nobody in Caldono’s Planning Department was surprised to learn that half of City Hall was sitting on a property with no land title. In the municipality of Caldono, six out of 10 parcels are informally owned, and this also applies to schools, health clinics, and municipal assets.

Nobody in Caldono’s Planning Department was surprised to learn that half of City Hall was sitting on a property with no land title. In the municipality of Caldono, six out of 10 parcels are informally owned, and this also applies to schools, health clinics, and municipal assets.

The end of the year brought good news for coffee growers in Northern Cauca. Seven families from Caldono received property titles to their coffee farms. Some of the families had initiated proceedings 10 years ago and had given up hope of ever obtaining a registered land title.

The end of the year brought good news for coffee growers in Northern Cauca. Seven families from Caldono received property titles to their coffee farms. Some of the families had initiated proceedings 10 years ago and had given up hope of ever obtaining a registered land title. “The most important thing that we can do for our coffee growers is protect their property. My recommendation is to move forward with companies and the government, seeking policies that facilitate land formalization through taxes. Coffee growers pay taxes, with this strategy, we can find several actors that can help.”

“The most important thing that we can do for our coffee growers is protect their property. My recommendation is to move forward with companies and the government, seeking policies that facilitate land formalization through taxes. Coffee growers pay taxes, with this strategy, we can find several actors that can help.” In Caldono, 66 percent of parcels are informally owned, indicating that some 1,900 coffee-growing families do not have a property title. Alba Ituyán and Ameiro Mosquera are coffee growers who started the land titling process almost ten years ago. Thanks to USAID and the National Coffee Federation, in 2023, they received a joint land title to their coffee farm.

In Caldono, 66 percent of parcels are informally owned, indicating that some 1,900 coffee-growing families do not have a property title. Alba Ituyán and Ameiro Mosquera are coffee growers who started the land titling process almost ten years ago. Thanks to USAID and the National Coffee Federation, in 2023, they received a joint land title to their coffee farm.

In each of the nine participating municipalities, USAID has trained public officials to give residents information about land titling and property issues. Jhojan Smith is an engineer working in La Macarena’s municipal administration, and when Meta’s regional team comes to work, he helps them reach the community.

In each of the nine participating municipalities, USAID has trained public officials to give residents information about land titling and property issues. Jhojan Smith is an engineer working in La Macarena’s municipal administration, and when Meta’s regional team comes to work, he helps them reach the community. Now that Raúl Moreno is the official owner of his property and has a registered land title backed by the government, he can support his family in other ways.

Now that Raúl Moreno is the official owner of his property and has a registered land title backed by the government, he can support his family in other ways.

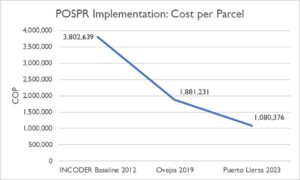

Since signing the 2016 Peace Accords, the government of Colombia has transformed rural land administration by adopting a model that puts the onus of formalizing rural property on government land agencies like the National Land Agency (ANT). With the support of USAID’s

Since signing the 2016 Peace Accords, the government of Colombia has transformed rural land administration by adopting a model that puts the onus of formalizing rural property on government land agencies like the National Land Agency (ANT). With the support of USAID’s  We have already used it, for example in the units that LFP delivered in Fuentedeoro and Puerto Lleras, we have already delivered land titles. In Santander de Quilichao we are going to identify the people and parcels that need to be formalized, that need land administration or legal tenure. We are going to make the processes quicker, more consistent, and especially produce results faster. What we aspire to is to avoid what happened to us in previous parcel sweeps, which were very long processes, too long for a single municipality, so we can gradually make progress.

We have already used it, for example in the units that LFP delivered in Fuentedeoro and Puerto Lleras, we have already delivered land titles. In Santander de Quilichao we are going to identify the people and parcels that need to be formalized, that need land administration or legal tenure. We are going to make the processes quicker, more consistent, and especially produce results faster. What we aspire to is to avoid what happened to us in previous parcel sweeps, which were very long processes, too long for a single municipality, so we can gradually make progress. Yes, we have implemented many changes, not only in the processes but also in simplifying forms, consolidating information collection tools, and issuing guidelines that are clear, not just for ANT employees but also for the parcel sweep operators. For example, before the ANT had 32 attention routes for land formalization, and we simplified the processes to 24 routes. Everything LFP has done to support the ANT with Rural Property and Land Use Planning translates to the possibility for a dignified life for rural Colombians.

Yes, we have implemented many changes, not only in the processes but also in simplifying forms, consolidating information collection tools, and issuing guidelines that are clear, not just for ANT employees but also for the parcel sweep operators. For example, before the ANT had 32 attention routes for land formalization, and we simplified the processes to 24 routes. Everything LFP has done to support the ANT with Rural Property and Land Use Planning translates to the possibility for a dignified life for rural Colombians.

Luz Mery Valdez is an iconic woman, who is defying gender stereotypes through her work as a cassava and yam farmer in the Montes de María region of Colombia. She works with the Association of United Women of San Isidro (AMUSI) in the municipality of El Carmen de Bolívar.

Luz Mery Valdez is an iconic woman, who is defying gender stereotypes through her work as a cassava and yam farmer in the Montes de María region of Colombia. She works with the Association of United Women of San Isidro (AMUSI) in the municipality of El Carmen de Bolívar. What have been the most visible changes since women have participated in farming activities?

What have been the most visible changes since women have participated in farming activities? What would you say to other women?

What would you say to other women?

As part of the 16 days of activism to end violence against women and girls, LFP talked to Judith Rodríguez, a member of

As part of the 16 days of activism to end violence against women and girls, LFP talked to Judith Rodríguez, a member of  In the Community Council, you share the land between members. Do you think the women who own land individually or jointly with their partners are as protected as you?

In the Community Council, you share the land between members. Do you think the women who own land individually or jointly with their partners are as protected as you? There are laws to stop men from selling common properties without the consent of their partners. Do you think there is a need to talk about these laws more widely?

There are laws to stop men from selling common properties without the consent of their partners. Do you think there is a need to talk about these laws more widely?

One early morning in 1994, Gloria Ester Buelvas was woken and told she had to leave her grandfather’s farm in San Pedro de Urabá, where she had lived 16 years of her life. Nearly three decades later, Buelvas still does not know why she and dozens of members of her family were threatened and forced to leave their hometown.

One early morning in 1994, Gloria Ester Buelvas was woken and told she had to leave her grandfather’s farm in San Pedro de Urabá, where she had lived 16 years of her life. Nearly three decades later, Buelvas still does not know why she and dozens of members of her family were threatened and forced to leave their hometown. Colombia’s Urabá region stretches from the border of Panama along the Caribbean coast and is famous for bananas and large cattle ranching estates. Over generations, the region became a textbook example of the type of class divisions between landless farmers and an elite land-owning class that fomented strife and erupted in brazen warfare between the leftist guerrillas and paramilitary groups in the nineties. Families like the Buelvas were caught in the middle, accused of helping or supporting one side or the other.

Colombia’s Urabá region stretches from the border of Panama along the Caribbean coast and is famous for bananas and large cattle ranching estates. Over generations, the region became a textbook example of the type of class divisions between landless farmers and an elite land-owning class that fomented strife and erupted in brazen warfare between the leftist guerrillas and paramilitary groups in the nineties. Families like the Buelvas were caught in the middle, accused of helping or supporting one side or the other. Over the years, the municipality provided relief, including improved roads and electricity, and the families rebuilt their lives. Gloria and her neighbors supported each other through subsistence agriculture, but none have ever obtained a land title for their property.

Over the years, the municipality provided relief, including improved roads and electricity, and the families rebuilt their lives. Gloria and her neighbors supported each other through subsistence agriculture, but none have ever obtained a land title for their property.  When the cadaster of Puerto Lleras was last updated in 2011, it included 2,300 properties. Following the implementation of the 2023 POSPR, the initiative surveyed over 4,600 properties, many of which are home to displaced families. More than half of these parcels are not recognized by the state but are ready to be formalized and issued a registered land title.

When the cadaster of Puerto Lleras was last updated in 2011, it included 2,300 properties. Following the implementation of the 2023 POSPR, the initiative surveyed over 4,600 properties, many of which are home to displaced families. More than half of these parcels are not recognized by the state but are ready to be formalized and issued a registered land title. Puerto Lleras is one of

Puerto Lleras is one of